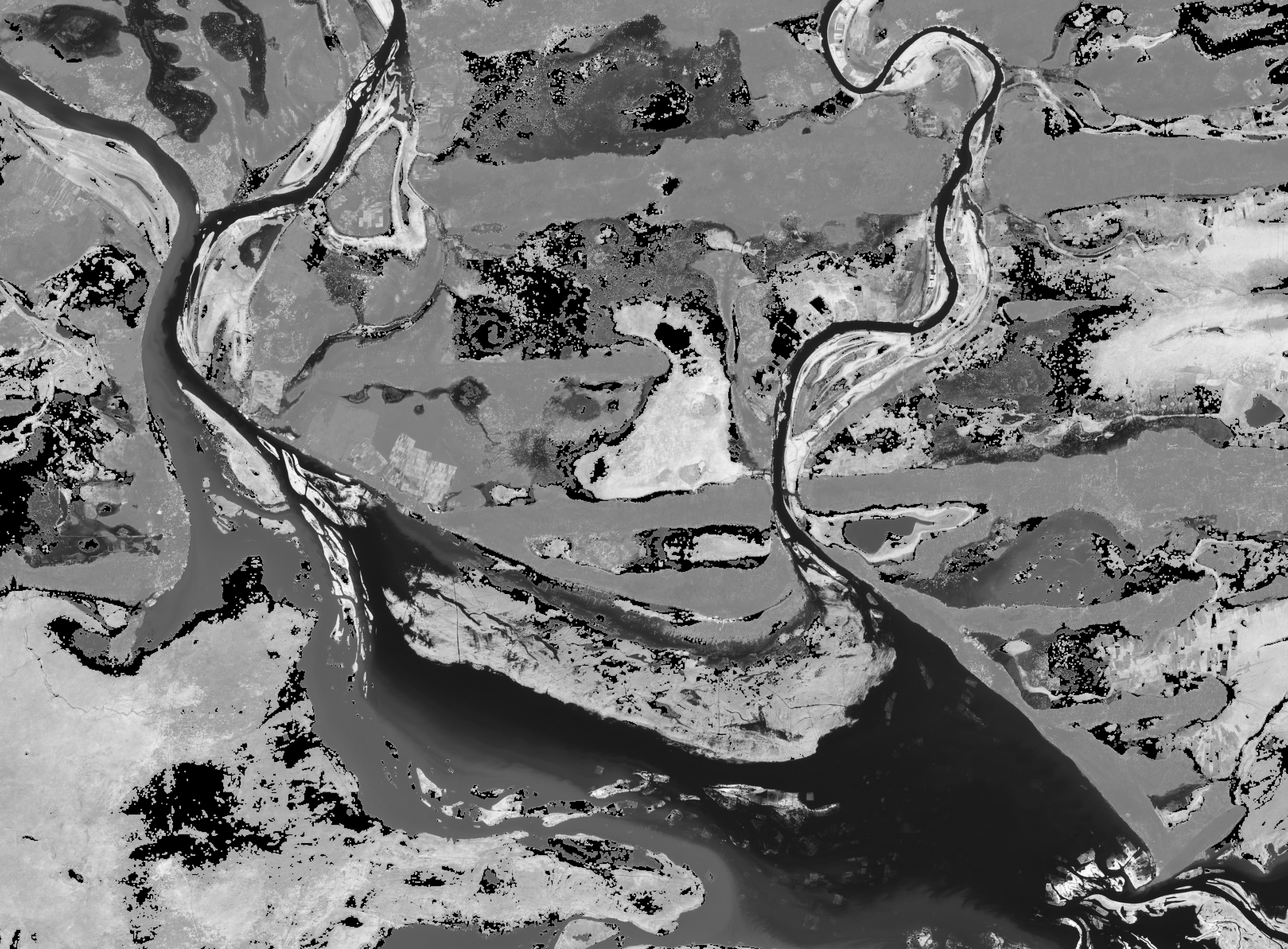

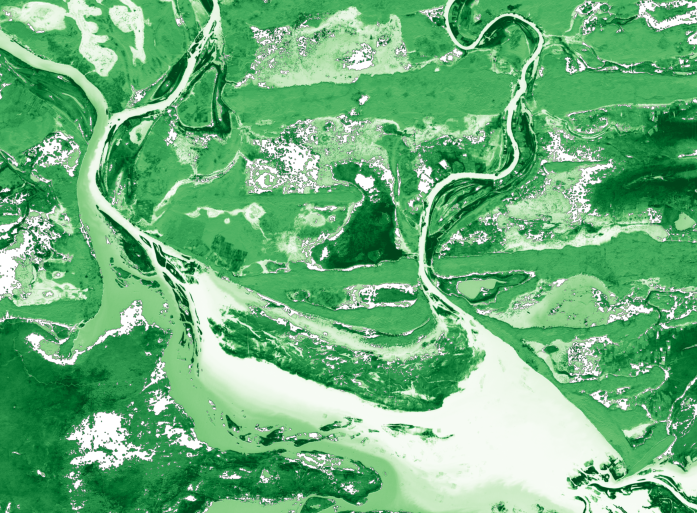

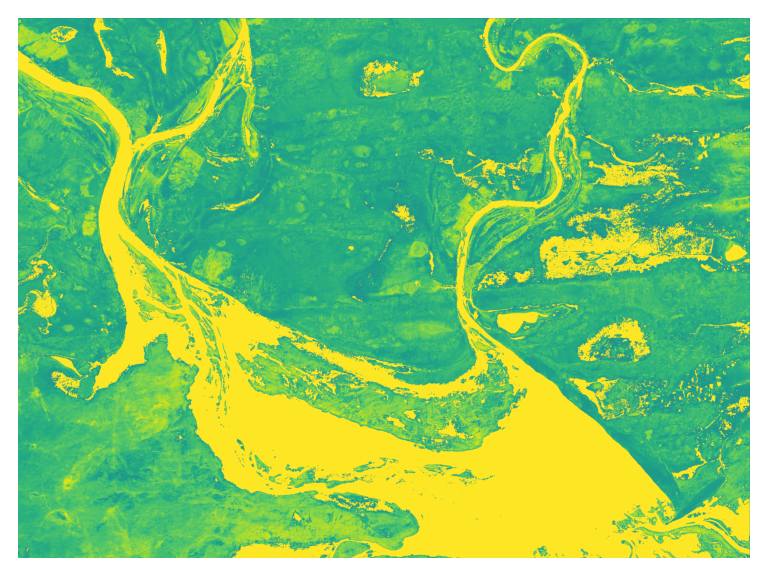

Sentinel-2 satellite preview of Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region, captured on 2025-12-29 from an altitude of approximately 786 km.

Statement of Problem

Desertification threatens the livelihoods of over 2 billion people worldwide, degrading 12 million hectares of productive land annually. As climate change intensifies droughts and extreme weather events, arid and semi-arid regions face unprecedented ecological stress. In Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region, the balance between sparse vegetation and expanding deserts hangs in the balance. Understanding vegetation health, soil exposure, and moisture stress is critical for guiding land restoration, sustainable grazing, and climate adaptation strategies. This analysis quantifies the current state of desert ecosystems in Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region, identifies high-risk areas for desertification, and tracks 5-year trends to reveal whether the land is recovering or degrading.

The Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region landscape, A representation image of this landscape. Image reference: Fatima Wourro, Amah Akodewou, Justin Kassi N'dja, Bruno Hérault, Re-greening the Sahel? Evaluating tree cover restoration strategies in Niger, Journal of Arid Environments, Volume 232 (2026), Article 105484. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2025.105484 ( ScienceDirect )

Understanding SAHEL - North of the Niger River, Mali

Why we chose this region

Desert and semi-arid lands cover over 40 percent of the Earth’s land surface and support the lives and livelihoods of more than 2 billion people.

These landscapes may look empty from a distance, but they are deeply connected to food, water, and survival for millions.

When land degrades here, the effects travel far beyond the desert itself.

The area north of the Niger River in Mali sits in one of the most sensitive parts of this global system. It lies in the Sahel, a narrow transition zone between greener farmland to the south and true desert to the north.

Rainfall is low and comes in short, unpredictable bursts.

Some years the rains arrive late, other years they fail almost completely.

The soil is light and fragile, and once plant cover is lost, it can quickly erode or turn barren.

People living in this region depend directly on the land. Farming is mostly rain-fed, with no large irrigation systems to fall back on.

Families grow crops during short rainy seasons and raise livestock that move with the land and seasons.

Trees are not planted casually. They are protected because they hold moisture, reduce soil loss, and provide food, shade, or fuel.

Traditional planting and land-care methods are shaped by survival, not convenience.

We chose this region because even small changes here matter. A slight gain or loss in vegetation can be an early sign of land stress, food insecurity, or recovery.

Satellite monitoring allows us to track these changes in a clear and repeatable way.

In places like north of the Niger River, where vegetation is sparse and rainfall is uncertain, continuous monitoring becomes an early warning system.

What happens here often signals what may soon happen across much of the Sahel and other dry regions of the world.

The Challenge of Measuring Sparse Vegetation

Vegetation in desert regions behaves very differently from forests or farmlands.

Most common satellite vegetation measures were created for places where plants grow thick and close together.

In dry regions like this, plants are scattered and much of the ground is bare soil.

This makes measurement tricky, because bare soil can sometimes reflect light in a way that looks like vegetation, even when there is very little growth.

To avoid this problem, desert monitoring uses vegetation measures that are adjusted for soil.

Indices like SAVI and MSAVI2 are designed to reduce the effect of exposed soil and give a clearer picture of real plant growth.

In this analysis, we combine several vegetation and moisture indicators to understand different aspects of the landscape in the Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region, including plant activity, greenness, and water stress.

By looking at quarterly data over the past five years, we are not just seeing how the land looks today, but how it is changing over time.

This helps us understand whether the land is slowly recovering or moving closer to degradation.

Executive Summary

Past (Last 5 Years)

Between 2021 and 2025, vegetation health in the Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region experienced significant fluctuations. The mean NDVI value dropped from 0.49 in early 2021 to 0.22 in mid-2025, indicating a decline in overall vegetation health. However, there was a slight recovery towards the end of 2025, with NDVI rising to 0.41. Moisture levels, as indicated by NDMI, also showed variability, with the lowest recorded mean of 0.47 in late 2025, down from 0.61 in early 2021. These trends highlight the region's vulnerability to drought and the impact on vegetation health.

Present (Current Status)

As of December 2025, the Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region shows a mixed picture of vegetation health. The mean NDVI stands at 0.09, indicating sparse vegetation cover. However, the SAVI mean of 0.13 suggests slightly better vegetation health when accounting for soil brightness. Alarmingly, 38% of the region falls into the highest desertification risk category (0.8-1.0), primarily in the northwestern zones. These areas require immediate attention to prevent further degradation.

Future (What Happens Next)

If current trends continue, the region may face worsening vegetation health and expanding desertification risk. Targeted interventions in high-risk zones, combined with drought-resistant vegetation strategies, are crucial. Monitoring and early action in areas showing declining trends will be essential to stabilize or reverse degradation. The next few years will be critical in determining the region's ecological future.

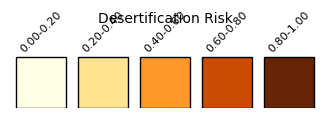

1. Sparse Vegetation Assessment: SAVI vs NDVI

1.1 SAVI Analysis (Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index)

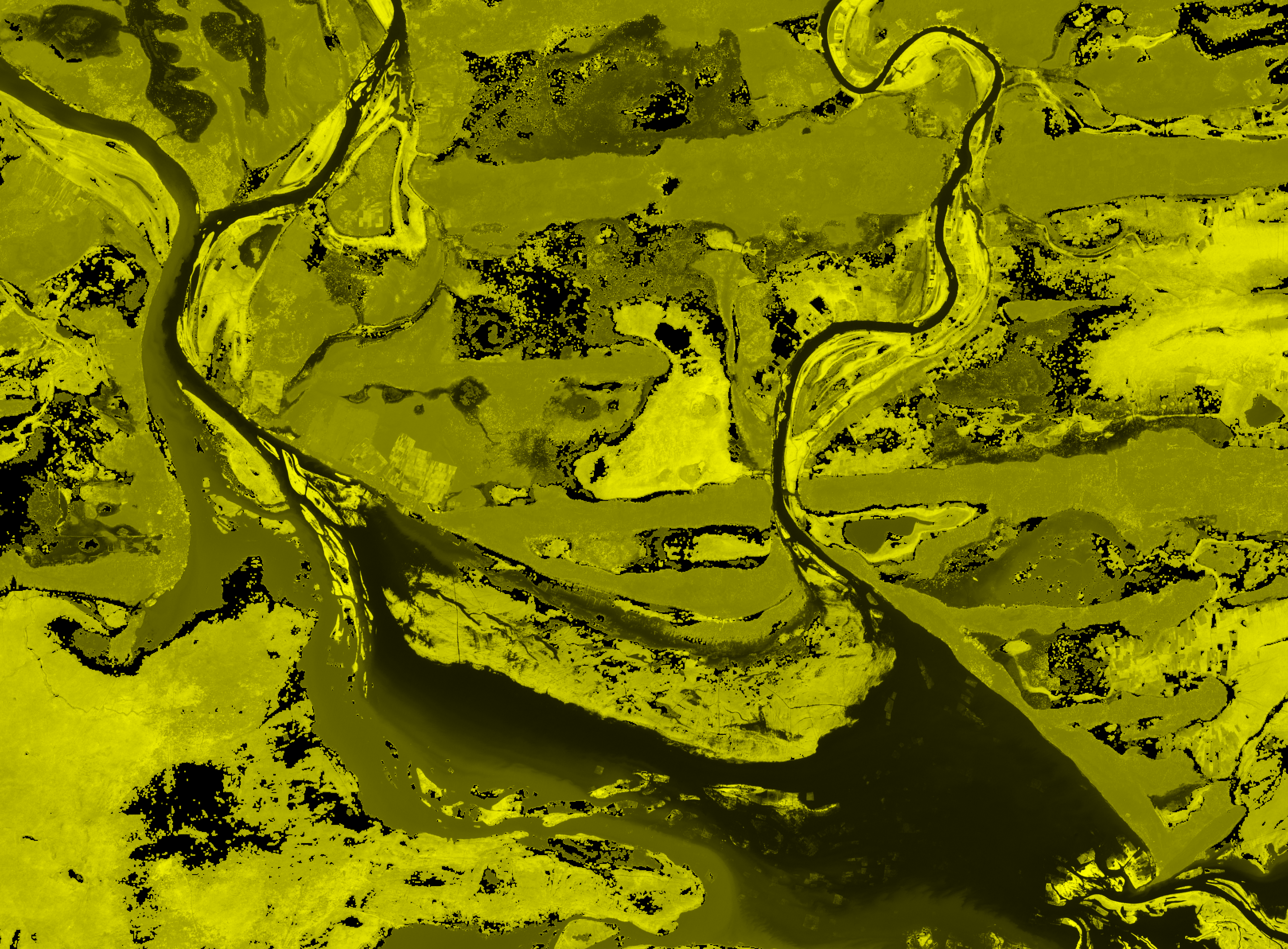

The SAVI statistics reveal a mean value of 0.13 and a median of 0.17, indicating moderate vegetation health when accounting for soil brightness. The standard deviation of 0.33 shows significant spatial variability. The SAVI color map highlights areas with higher vegetation cover, particularly in the southern regions. The greyscale map further emphasizes these patterns, showing a clear contrast between vegetated and non-vegetated areas. SAVI's soil adjustment is critical in this region, where bare soil can skew standard vegetation indices.

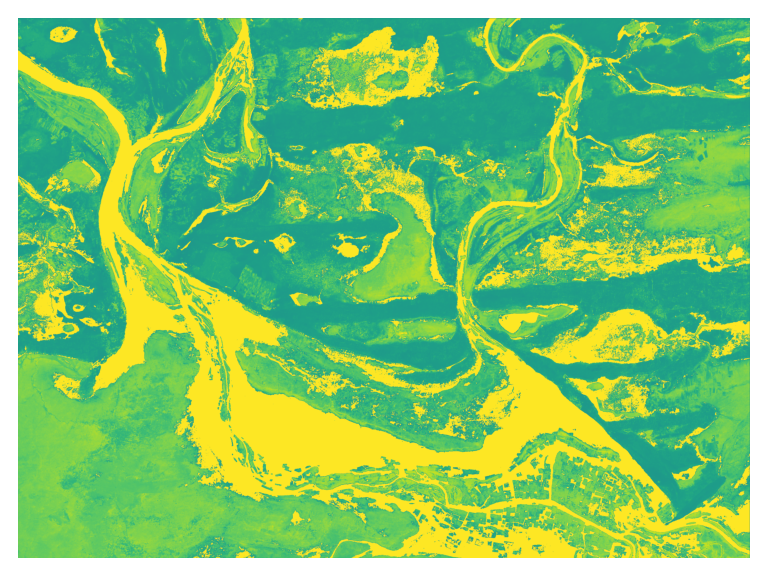

1.2 NDVI Analysis (Standard Vegetation Index)

NDVI statistics show a lower mean of 0.09 and a median of 0.11, indicating sparser vegetation compared to SAVI. This discrepancy highlights NDVI's limitations in areas with bright soil, where it may underestimate vegetation cover. The NDVI maps confirm this, showing less vegetated areas compared to the SAVI maps. This underscores the importance of using soil-adjusted indices in arid regions.

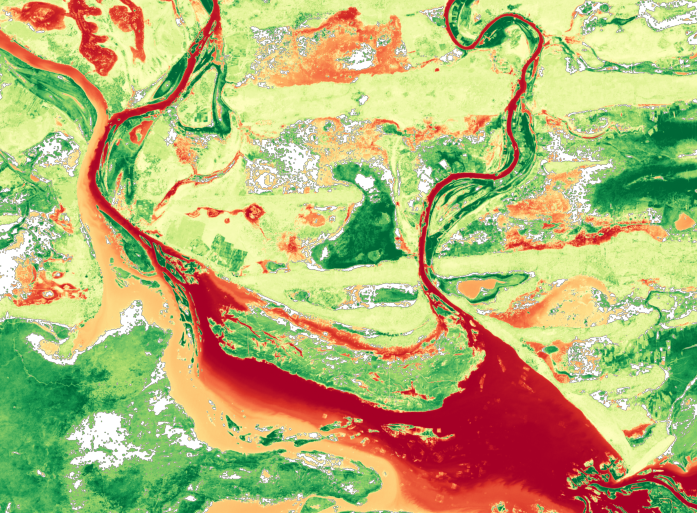

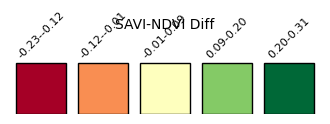

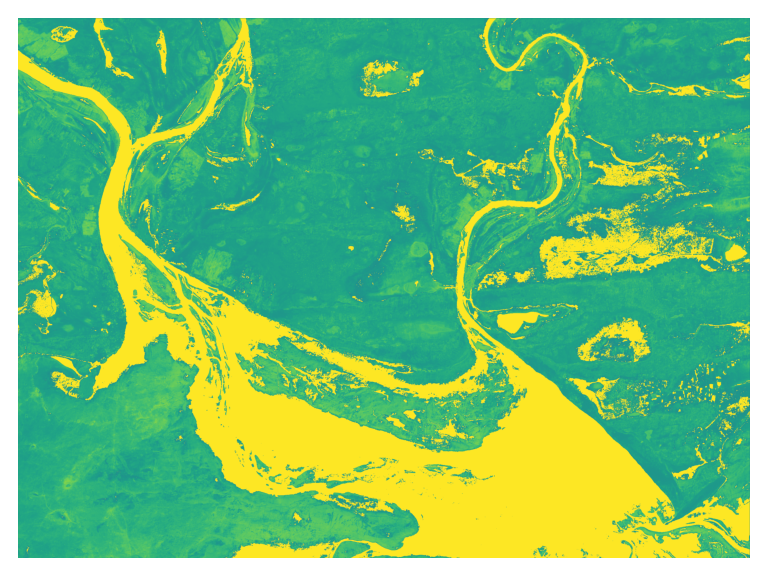

1.3 SAVI vs NDVI: Why Soil Adjustment Matters

The SAVI-NDVI difference bins reveal where SAVI detects vegetation that NDVI misses due to soil brightness. Approximately 34% of the region falls into the -0.01 to 0.09 difference bin, indicating areas where SAVI shows moderate vegetation cover that NDVI underestimates. The difference map and legend confirm these patterns, showing that SAVI identifies more vegetated areas, especially in the central and southern regions. This soil adjustment is crucial for accurate vegetation assessment in the Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region.

SAVI Color Visualization (Soil-Adjusted)

SAVI Greyscale (Index Values)

NDVI Color Visualization (Standard)

NDVI Greyscale (Index Values)

SAVI-NDVI Difference Map (Shows where soil adjustment reveals hidden vegetation)

Combined SAVI-NDVI Overlay

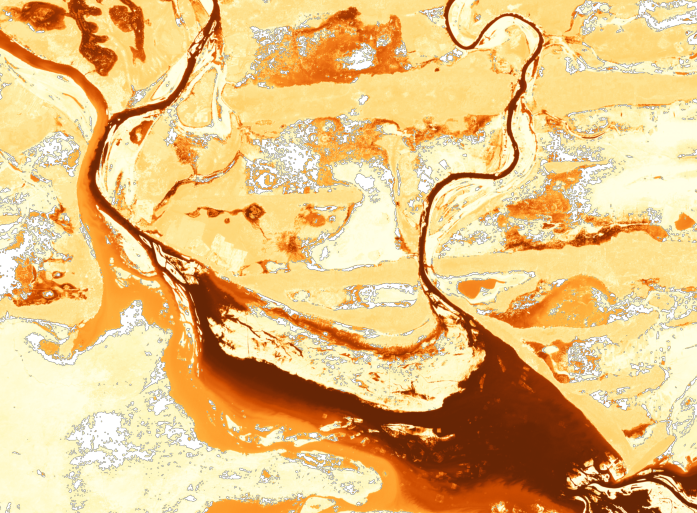

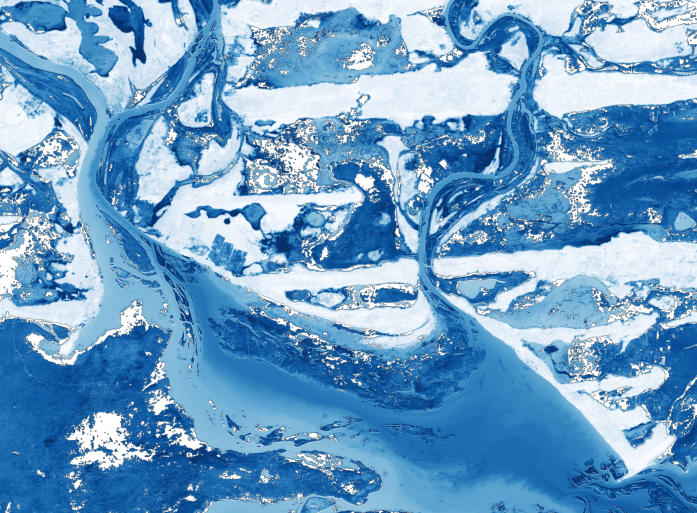

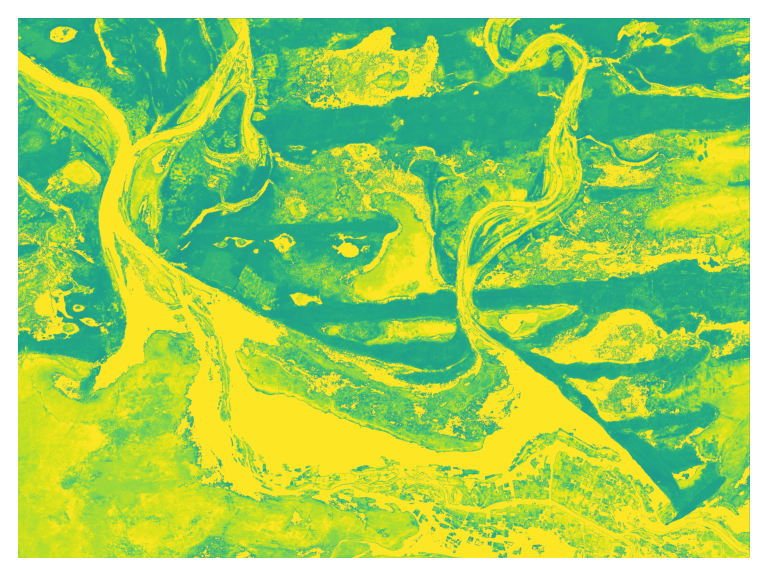

2. Desertification Risk Analysis

2.1 Risk Zone Distribution

The desertification risk bins identify high-risk zones (0.8-1.0) covering 9.6% of the region, primarily in the northwest. Moderate-risk zones (0.4-0.6) account for 9.3%, while low-risk zones (0.0-0.2) make up 38%. These high-risk areas are characterized by severe soil exposure and low vegetation cover. Factors contributing to high risk include overgrazing, deforestation, and climate variability. The risk map and legend highlight these zones, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions.

2.2 Geographic Patterns & Critical Areas

Spatial patterns of desertification risk show a clear gradient, with the highest risks in the northwest and lower risks in the southeast. Critical areas include corridors of degradation along the Niger River, where human activities and natural factors combine to exacerbate desertification. The overlay visualization confirms these patterns, showing a clear delineation between high-risk and low-risk zones.

2.3 Key Findings from Dashboard

- Mean desertification risk score: 0.29

- 38% of the region in the lowest risk category (0.0-0.2)

- 9.6% in the highest risk category (0.8-1.0)

- Standard deviation of risk scores: 0.23, indicating significant variability

Desertification Risk Map (Red = high risk zones requiring intervention)

5-Year Vegetation Trends (2021-2025)

Quarterly satellite observations reveal how vegetation and moisture levels have changed over the past 5 years. These trends help identify long-term degradation or recovery patterns.

NDVI vs SAVI Trends

Quarterly mean NDVI and SAVI values showing seasonal cycles and long-term trends.

Vegetation Moisture Stress (NDMI)

NDMI tracks vegetation water content. Lower values indicate moisture stress.

5-Year Change Summary

- NDVI Change: -0.079 (2021-01-02 to 2025-10-03)

- SAVI Change: -0.118 (soil-adjusted vegetation)

- NDMI Change: -0.135 (moisture stress indicator)

Note: Positive changes indicate vegetation recovery. Negative changes suggest degradation or drought stress.

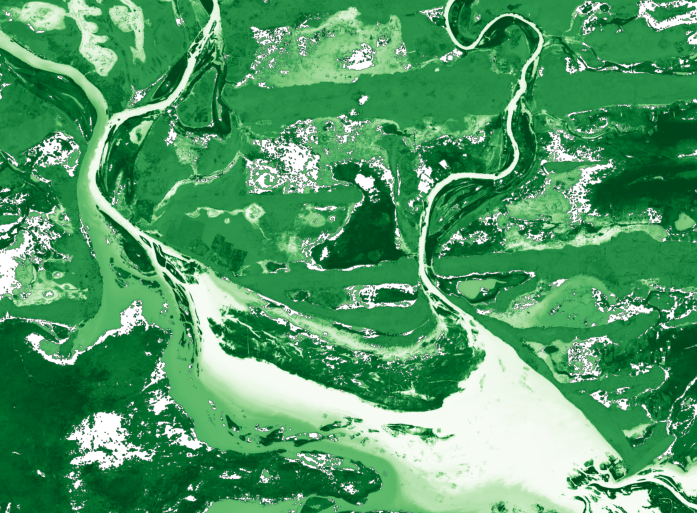

3. Vegetation Health & Moisture Stress

3.1 Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI)

EVI statistics show a mean of 0.47 and a median of 0.42, indicating better vegetation health compared to NDVI and SAVI. EVI's correction for atmospheric conditions and canopy background makes it more reliable in this region. The EVI map confirms healthier vegetation in the southern and eastern areas, aligning with SAVI but showing more robust vegetation signals.

3.2 Moisture Stress Assessment (NDMI & MSAVI2)

NDMI statistics reveal a mean of 0.07, indicating moderate moisture stress across the region. Lower values are concentrated in the northwest, aligning with high desertification risk zones. MSAVI2, with a mean of 0.07, further refines soil adjustment, showing similar patterns. Both indices highlight moisture-stressed areas, particularly in the northwest, where vegetation health is most at risk. The NDMI and MSAVI2 maps confirm these patterns, showing clear moisture stress gradients.

3.3 Chlorophyll Content (NDRE)

NDRE statistics show a mean of 0.02, indicating low chlorophyll content and vegetation stress. Lower values are concentrated in the northwest, aligning with other stress indicators. The NDRE map confirms these patterns, showing areas with the lowest chlorophyll content and highest vegetation stress.

EVI (Enhanced Vegetation Index)

MSAVI2 (Modified SAVI)

NDMI (Moisture Stress)

NDRE (Chlorophyll Content Indicator)

Visual Comparison: 2021 vs 2025

Side-by-side comparisons show spatial patterns of vegetation change over 5 years. Green areas indicate vegetation; brown/red areas indicate bare soil or sparse vegetation.

NDVI: 2021 Q1 vs 2025 Q4

2021 Q1 (Baseline)

2025 Q4 (Current)

SAVI: 2021 Q1 vs 2025 Q4

2021 Q1 (Baseline)

2025 Q4 (Current)

Visual Analysis: Compare green (vegetation) vs brown/red (bare soil) areas. Areas shifting from brown to green indicate recovery; green to brown indicates degradation.

4. Long-Term Trends & Land Management Recommendations

4.1 5-Year Trends (2021-2025)

Over the past 5 years, the Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region has experienced fluctuating vegetation health. NDVI mean values dropped from 0.49 in early 2021 to 0.22 in mid-2025, indicating a decline in overall vegetation health. However, there was a slight recovery towards the end of 2025, with NDVI rising to 0.41. SAVI trends showed a similar pattern, with a decline from 0.61 to 0.28, followed by a recovery to 0.49. NDMI values also fluctuated, with the lowest recorded mean of 0.47 in late 2025, down from 0.61 in early 2021. These trends highlight the region's vulnerability to drought and the impact on vegetation health.

4.2 What's Working Well

- Areas in the southeast showing stable or improving vegetation health, as indicated by higher NDVI and SAVI values.

- Periods of recovery in late 2025, with NDVI and SAVI values rising despite overall trends.

4.3 Critical Challenges

- Expanding high-risk desertification zones in the northwest, with 9.6% of the region now in the highest risk category.

- Declining vegetation health in specific areas, particularly in the central regions, as indicated by lower NDVI and SAVI values.

- Increasing moisture stress, with NDMI values dropping to 0.47 in late 2025, indicating severe drought conditions.

4.4 Evidence-Based Recommendations

- Prioritize restoration efforts in the high-risk northwest zones identified in Section 2, focusing on soil stabilization and vegetation planting.

- Implement drought-resistant vegetation strategies in moisture-stressed areas identified in Section 3, particularly those with low NDMI and MSAVI2 values.

- Monitor areas showing declining trends in historical data, particularly those with consistently low NDVI and SAVI values, to enable early intervention.

Why These Indices Matter for Deserts

Core Indices for Desert Analysis

Desert ecosystems require specialized remote sensing approaches that account for sparse vegetation and high soil reflectance. This analysis uses six complementary indices:

Understanding SAVI and Soil Adjustment

SAVI (Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index) was specifically developed for areas with sparse vegetation. It includes a soil brightness correction factor (L=0.5) that reduces the influence of exposed soil on vegetation measurements. In deserts, SAVI values typically range from 0.1 to 0.4, with higher values indicating denser vegetation patches. SAVI is more reliable than NDVI in arid regions where vegetation cover is less than 40%.

MSAVI2 (Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index) improves on SAVI by using a variable soil adjustment factor that adapts to different soil brightnesses. This makes it more accurate across diverse desert landscapes with varying soil types.

Standard and Enhanced Vegetation Indices

NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) measures the difference between near-infrared and red light reflectance. While less reliable in deserts due to soil contamination, NDVI is included for comparison and to maintain consistency with global vegetation monitoring standards. Typical desert NDVI ranges: 0.1-0.2 = bare soil with scattered vegetation; 0.2-0.4 = sparse vegetation; >0.4 = moderate vegetation.

EVI (Enhanced Vegetation Index) corrects for atmospheric conditions and canopy background noise, making it more sensitive in areas with moderate vegetation. EVI is particularly useful for detecting subtle changes in vegetation health that NDVI might miss.

Moisture and Stress Indicators

NDMI (Normalized Difference Moisture Index) measures vegetation water content by comparing near-infrared and shortwave infrared reflectance. In deserts, NDMI is a critical early warning indicator: declining NDMI values signal drought stress before visible browning occurs. Values <0 indicate severe moisture stress; 0-0.2 = moderate stress; >0.2 = adequate moisture.

NDRE (Normalized Difference Red Edge) uses the red edge band (Band 5) to measure chlorophyll content. It is highly sensitive to vegetation stress in sparse canopies and can detect early senescence (aging/dying vegetation) before it appears in standard indices.

Desertification Risk Assessment

The Desertification Risk Index is a composite metric that combines vegetation indices, soil exposure, and moisture stress to identify areas at high risk of land degradation. High-risk zones (typically where SAVI < 0.15 and NDMI < 0) require immediate intervention to prevent irreversible desertification.

Data & Methods

Data Sources

- Satellite: Sentinel-2A Level-2A (atmospherically corrected)

- Provider: Microsoft Planetary Computer

- Observation Date: 2025-12-29

- Cloud Cover: 0.008076%

- Spatial Resolution: 10 meters (NDVI, SAVI, EVI), 20 meters (NDMI, MSAVI2, NDRE, resampled to 10m)

Index Calculations

- NDVI = (NIR - Red) / (NIR + Red) using Bands 8 and 4

- SAVI = ((NIR - Red) / (NIR + Red + L)) × (1 + L), where L = 0.5 (soil brightness correction factor)

- MSAVI2 = (2×NIR + 1 - √((2×NIR + 1)² - 8×(NIR - Red))) / 2

- EVI = 2.5 × ((NIR - Red) / (NIR + 6×Red - 7.5×Blue + 1))

- NDMI = (NIR - SWIR1) / (NIR + SWIR1) using Bands 8 and 11

- NDRE = (NIR - RedEdge) / (NIR + RedEdge) using Bands 8 and 5

- SAVI-NDVI Difference = SAVI - NDVI (reveals soil adjustment impact)

- Desertification Risk = Composite metric combining low vegetation, high soil exposure, and moisture stress

Historical Trend Analysis

This analysis includes 5 years of quarterly satellite observations (2021-2025), providing

20 data points for trend analysis. Quarterly observations capture seasonal variability

(wet/dry seasons) and long-term degradation or recovery patterns. Historical data is

stored at: trees-and-data/greenery-monitoring-past-data/ with quarterly

folders (Q1: January, Q2: April, Q3: July, Q4: October).

Processing Workflow

Images were processed using Python with the pystac-client and rasterio

libraries. Cloud masking was applied using the Scene Classification Layer (SCL). Statistics

were computed using rasterio zonal statistics and exported as JSON for

analysis. All geospatial outputs are provided as Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFFs (COGs) for

efficient web access and GIS integration.

Limitations & Considerations

- Analysis represents quarterly snapshots; higher temporal resolution would capture intra-seasonal dynamics

- Cloud cover and atmospheric conditions affect image quality, especially during monsoon seasons

- 10-meter resolution may not capture individual shrubs or small vegetation patches

- Study area boundaries reflect the satellite image crop, not administrative boundaries

- Soil-adjusted indices (SAVI, MSAVI2) assume moderate soil brightness; extreme soil types (white salt flats, black basalt) may require calibration

- Desertification risk is inferred from spectral indices; ground validation recommended for restoration planning

- Historical trends assume consistent processing methods; changes in Sentinel-2 calibration over time are minimal but not zero

Download Data & Maps

Images & Visualizations

- NDVI Color Map (PNG)

- SAVI Color Map (PNG)

- MSAVI2 Color Map (PNG)

- EVI Color Map (PNG)

- NDMI Color Map (PNG)

- NDRE Color Map (PNG)

- SAVI-NDVI Difference Map (PNG)

- Difference Map Legend (PNG)

- Desertification Risk Map (PNG)

- Risk Map Legend (PNG)

- Combined Overlay (PNG)

Geospatial Data (Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFFs)

- NDVI GeoTIFF (COG)

- SAVI GeoTIFF (COG)

- MSAVI2 GeoTIFF (COG)

- EVI GeoTIFF (COG)

- NDMI GeoTIFF (COG)

- NDRE GeoTIFF (COG)

- Difference GeoTIFF (COG)

- Risk GeoTIFF (COG)

Statistical Data

README Note

Our Mission: We want this research dataset brief to be Simple, Authentic, and Repeatable.

1. Title of the Dataset

Desert Greening & Desertification Risk Assessment

2. What This Dataset Is About

This dataset was created to help anyone understand how vegetation and green cover in this region is changing over time. It brings together processed satellite data, simple calculations, and a few observations that give the bigger picture.

3. Why This Dataset Matters

At I Hug Trees, we believe that Geospatial Satellite imagery and processed data should be accessible

to everyone. While grounded in scientific principles, outputs are presented in accessible formats so

that technical imagery and calculations resonate with ordinary people and communities.

Because only

when it is relatable, can it tell clear stories about our greenery and urban life: shaping how we

live, how we breathe, and how we cope with rising heat.

This dataset tries to make that easier. Whether you are a researcher, policy maker, student or just curious about the environment, these numbers and images help you see trends that are not obvious at first glance.

4. Source of the Data

- Satellite: Sentinel-2

- Provider: Microsoft Planetary Computer

- Acquisition Window: Past 60 days (filtered by cloud cover)

- Cloud Cover Threshold: < 30%

- Initial Tile Discovery: Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem browser

5. How the Data Was Processed

Basic Preprocessing:

It is important to get the right tile from the Sentinel-2 database for imagery processing. The browser feature from the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem helped us identify the correct tile, its bounds, and the subset coordinates needed for extraction. It is always essential to double-check the preview image to verify that the fetched tile truly corresponds to the target region.

Next, we used an AWS Lambda environment for the bounds-discovery phase. This step involved fetching band data from the Microsoft Planetary Computer for dates where cloud cover was below 30% within the past 60 days. Once the acquisition date met this condition, we moved to AWS EC2 server scripts written in Python to download raw band data and process them into COGs (Cloud Optimised GeoTIFFs) along with additional indices.

These processed COGs and index outputs are then used for image displays, NDVI interpretation, and HTML digest features published on our platform. All indices raw value outputs are in JSON files for easy repeatable processing. We currently run this workflow on a quarterly schedule for each identified region.

Cloud Masking:

This dataset uses Sentinel-2's Scene Classification Layer (SCL) to remove pixels affected by clouds, shadows, haze, and saturation. Only surface-clear classes are kept, ensuring that the vegetation indices are calculated from clean, reliable pixels. The masking is applied at the pixel level, meaning every index (NDVI, EVI, etc.) is computed only on valid areas after stripping away noisy regions. This results in more trustworthy COGs, cleaner previews, and more meaningful temporal comparisons.

Calculation Formulas Used:

NDVI = (NIR − Red) ÷ (NIR + Red)EVI = 2.5 × (NIR − Red) ÷ (NIR + 6×Red − 7.5×Blue + 1)NDWI = (Green − NIR) ÷ (Green + NIR)SAVI = (NIR − Red) ÷ (NIR + Red + L) × (1 + L)MSAVI2 = [2×NIR + 1 − √((2×NIR + 1)² − 8×(NIR − Red))] ÷ 2

Tools Used:

Data Source: Microsoft Planetary Computer (Sentinel-2 L2A), rasterio, GDAL

Computation: Python 3, NumPy, SciPy, Pillow, Rasterio, rio-cogeo

AWS Pipeline: Lambda (triggers), EC2 (processing), S3 (storage), Bedrock (AI summaries)

Mapping: Leaflet.js, tile layers served from S3

Automation: Python boto3, Cron (EC2 quarterly jobs)

6. File Contents

The dataset includes metadata.json with satellite tile information, various index outputs

(NDVI, EVI, NDWI, NDBI, MNDWI, NDMI), and statistical summaries. Please find the detailed list of files

available for download in the Download Data & Maps section below.

7. How to Use This Dataset

You can explore the NDVI trends, plug the json file into your favourite tool, build visualisations, or compare it with earlier datasets. It's created to be flexible.

8. Leveraging AI

AI helped speed up some parts of the work, like spotting unusual patterns, creating brief insights, and checking for inconsistencies. All metadata and bin-statistics JSON files were loaded and parsed into structured dictionaries, ensuring the AI receives clean, context-rich inputs for stable summarisation and interpretation.

9. Limitations & Things to Keep in Mind

- Cloud cover may affect accuracy

- NDVI has known limitations

- Spatial resolution is 10 meters

- Some patterns may need ground truth validation

10. License / Permissions

Please refer to the How to Cite This Analysis section below for citation guidelines. This dataset is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

11. Contact

For any questions, collaborations, or clarifications, feel free to reach out at: nature@ihugtrees.org

How to Cite This Analysis

Recommended Citation

Yaragarla, R. (2026). Desert Greening & Desertification Risk Assessment: Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region. I Hug Trees. Retrieved from https://ihugtrees.org/trees-and-data/desert-greening/Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region/2026/01/02/digest.html

Satellite data: Copernicus Sentinel-2 (ESA), processed via Microsoft Planetary Computer.

BibTeX Entry

@misc{ihugtrees_desert_sahelmalinorthofnigerriverregion_2026,

author = {Yaragarla, Ramkumar},

title = {Desert Greening \& Desertification Risk Assessment: Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region},

year = {2026},

publisher = {I Hug Trees},

url = {https://ihugtrees.org/trees-and-data/desert-greening/Sahel-Mali-North-of-Niger-River-region/2026/01/02/digest.html},

note = {Satellite data: Copernicus Sentinel-2}

}

License

This analysis and associated datasets are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share and adapt this work with appropriate attribution.

Planetary Computer Citation

If using Microsoft Planetary Computer data, please cite: microsoft/PlanetaryComputer (2022)